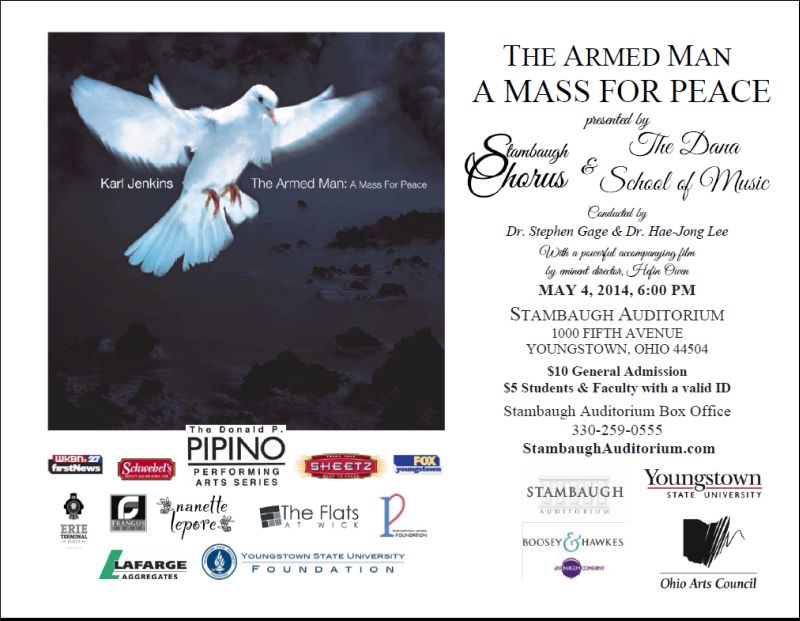

Download The Armed Man Poster (PDF)

Download The Armed Man Poster (PDF)

PROGRAM

Glory Days David Morgan

Winter Sky Stephen Barr

INTRODUCTION OF SENIOR WIND ENSEMBLE MEMBERS

Slava! Leonard Bernstein/arr. Clare Grundman

YSU Wind Ensemble

Stephen Gage, Director

INTERMISSION

Prayer of Children Kurt Bestor/arr. Andrea Clause

Stambaugh Chorus & Dana Symphonic Choir

Hae-Jong Lee, Director

The Armed Men: A Mass for Peace Karl Jenkins (b. 1944)

1. The Armed Man

2. Call to Prayer

3. Kyrie

4. Save Me from Bloody Men

5. Sanctus

6. Hymn Before Action

7. Charge!

8. Angry Flames

9. Torches

10. Agnus Dei

11. Now the Guns Have Stopped

12. Benedictus

13. Better Is Peace

With Accompanying Film by OPUS, Hefin Owen, producer

Rebecca Enlow, soprano (3, 13); Lisa Gonzalez, soprano (8);

Kathryn Kramer, mezzo-soprano (8, 11, 13)

Victor Cardamone, tenor (8, 13); Raymond Wagner Jr. (8 & 13), baritone

YSU Wind Ensemble

Stambaugh Chorus & Dana Symphonic Choir

Hae-Jong Lee, conductor

PROGRAM NOTES

Prayer of Children:

The Emmy-Award-winning composer Kurt Bestor notes about the story behind the song Prayer of Children: “Having lived in this now war-torn country back in the late 1970’s, I grew to love the people with whom I lived. It didn’t matter to me their ethnic origin – Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian – they were all just happy fun people to me and I counted as friends people from each region. Of course, I was always aware of the bigotry and ethnic differences that bubbled just below the surface, but I always hoped that the peace this rich country enjoyed would continue indefinitely. Obviously that didn’t happen.

When Yugoslavian President Josip Broz Tito died, different political factions jockeyed for position and the inevitable happened – civil war. Suddenly my friends were pitted against each other. Serbian brother wouldn’t talk to Croatian sister-in-law. Bosnian mother disowned Serbian son-in-law and so it went. Meanwhile, all I could do was stay glued to the TV back in the US and sink deeper in a sense of hopelessness.

Finally, one night I began channeling these deep feelings into a wordless melody. Then little by little I added words….Can you hear….? Can you feel……? I started with these feelings – sensations that the children struggling to live in this difficult time might be feeling. Serbian, Croatian, and Bosnian children all felt the same feelings of confusion and sadness and it was for them that I was writing this song.”

The Armed Man:

The Mass begins with a marching army and the beat of military drums, the orchestra gradually building to the choir’s entrance, singing the 15th-century theme tune – The Armed Man. After the scene is set, the style and pace changes and we are prepared for reflection by first the Moslem Call to Prayer (Adhaan) and then the Kyrie, which pays homage to the past by quoting (in the Christe eleison) from Palestrina’s setting of L’Homme armé. Next, to a plainsong setting, we hear words from the Psalms asking for God’s help against our enemies. The Sanctus that follows is full of menace, and has a primeval, tribal character that adds to its power. The menace grows in the next movement as Kipling’s Hymn Before Action builds to its final devastating line “Lord grant us strength to die.”

War is now inevitable. The Charge! opens with a seductive paean to martial glory, which is followed by the inevitable consequence – war in all its uncontrolled cacophony of destruction, then the eerie silence of the battlefield after the battle and, finally, the burial of the dead. Surely nothing can be worse than this? But think again. At the very center of the work is the Angry Flames, an excerpt from a poem about the horrors of the atom bomb attack on Hiroshima written by a poet who was there at the time and died in 1953 of leukemia brought on by exposure to radiation. But if we think that the obscenity of this mass destruction is new to our consciousness, we must reconsider as we listen, to the eerily similar passage from the ancient Indian epic the Mahàbharàta.

From the horror of mass destruction the work turns to remember that one death is one too many, that each human life is sacred and unique. First the Agnus Dei, with its lyrical chorale theme, reminds us of Christ’s ultimate sacrifice and this is followed by an elegiac setting of some lines I wrote (to accompany one of the dramatic interpretations we use in the museum) about the feelings of loss and guilt that so many of the survivors of the First World War felt when they came home but their friends did not.

Even the survivors can be hurt to destruction by war. The Benedictus heals those wounds in its slow and stately affirmation of faith and leads us to the final, positive, climax of the work. This begins back where we started in the 15th century with Lancelot and Guinevere’s declaration, born of bitter experience, that peace is better than war. The menace of the ‘Armed Man’ theme returns and vies for a time with Malory’s desire for peace. But time moves on and we come to our moment of commitment. Do we want the new millennium to be like the last? Or do we join with Tennyson when he tells us to “Ring out the thousand wars of old, Ring in the thousand years of peace”? It may seem an impossible dream, we may not have begun too well, but the Mass ends with the affirmation from Revelations that change is possible, that sorrow, pain and death can be overcome. Dona nobis pacem.

Program note by Guy Wilson, former Master of the Armories